Rebuttal to Dr. Neto’s Medium Post on “Fewer Hospitals, Better Healthcare”

Similar Symptoms, Wrong Diagnosis

I’m not a health expert, nor even close to being one, but if there’s something I know how to do, it’s sniffing out or continuing 1Twitter agendas. Twitter agendas are tricky, defining it will be hard and probably makes my rambling less coherent but to be clear on agendas, everyone has one. The motives behind it don't matter. A good agenda is always valid i.e. factual or merely opinionated. Every response to an agenda is an agenda. And for some useless reason, I'm good at spotting these. Not that there's anything inherently bad with agendas, but they all can't be taken seriously; and you risk being frequently ignored or even overstretching issues. (Depending on the response to this, I’d probably write on Twitter agendas on their own.)

Dr. Neto’s Medium post is a case of Twitter agenda and very good enough it's a policy debate and made it beyond Twitter. It began with a tweet criticizing Peter Obi’s record on hospitals. That was clearly an agenda, a political agenda. His response arguing that Akwa Ibom should close hospitals was also an agenda because as I have said, every response to an agenda is and agenda and it's either for or against. And this was also political, whether he admits it or not. The problem is not that it’s political. The problem is that it dresses up a political agenda as a policy argument and in doing so, it misdiagnoses Nigeria’s healthcare crisis.

The Political Origin of the Argument

The first tweet claimed it's ridiculous for some communities to be getting their first hospital implying Peter Obi underperformed. That was an agenda against Peter Obi.

Then came a Neto's quote, in turn, was an agenda defending Obi. The tweet didn't mention Peter Obi at all, but the agenda was clear as day even though it was spun out as some real policy debate on hospital proliferation and how he would close down more hospitals in Akwa Ibom so as to focus on few, making it look like Obi’s strategy was part of some grand “fewer but better hospitals” approach, which wasn't the case when he was Governor. (We can debate that another time)

That’s disingenuous. If Neto wanted to argue healthcare policy and not trying to carry water for Peter Obi, he could have done so on a neutral tweet or one not referring to Obi. For instance same point could have been made on the real post of the unveiling of the new hospital on Anambra’s government official handle. That wounld’t have made it less of an agenda or political but could have been argued as not an Obi defence. Could also have been a standalone tweet, the fact that he didn’t shows where his argument really came from: politics, not policy and an agenda to defend Peter Obi.

Denmark vs. Nigeria: The False Analogy

From reading his article it was obvious this idea wasn't new for him or came as a result of the tweet, rather was something he always had. Dr. Neto’s frustration comes from a very human place, the painful loss of his cousin. Despite living in Akwa Ibom, a state with hundreds of healthcare centers, his cousin was bounced from one hospital to another, each turning him away because they lacked the equipment or staff to manage his case. By the time he reached a private facility, it was too late.

That tragedy is real, and it illustrates the brokenness of our healthcare system. But Neto’s conclusion that Nigeria has “too many hospitals” and should close them down to be able to concentrate resource on few is him mistaking similar symptoms for the same disease as Denmark. For starters we already focus on few but it's not obvious to him because our problems won't be solved that way.

Neto’s main case is that Denmark once had too many hospitals, shut some down, and got better outcomes. He suggests Akwa Ibom should do the same. This sounds smart until you actually look at the facts beyond the surface.

Denmark had excess capacity. In the 1970s, Denmark had about 10 beds per 1,000 people. Before their 2007 reform, they still had around 7 beds per 1,000. They reduced hospitals from 42 (96 sites) to 21 (68 sites), consolidating services into stronger regional hubs. Even after cuts, they have 2.6 beds per 1,000 today. That's very far from our problem.

Nigeria operates from scarcity. We have only 0.5 beds per 1,000 people. Akwa Ibom’s 42 hospitals are underfunded not because they are too many, but because the state doesn’t have enough resources. Closing them wouldn’t free up meaningful funds because they already get crumbs.

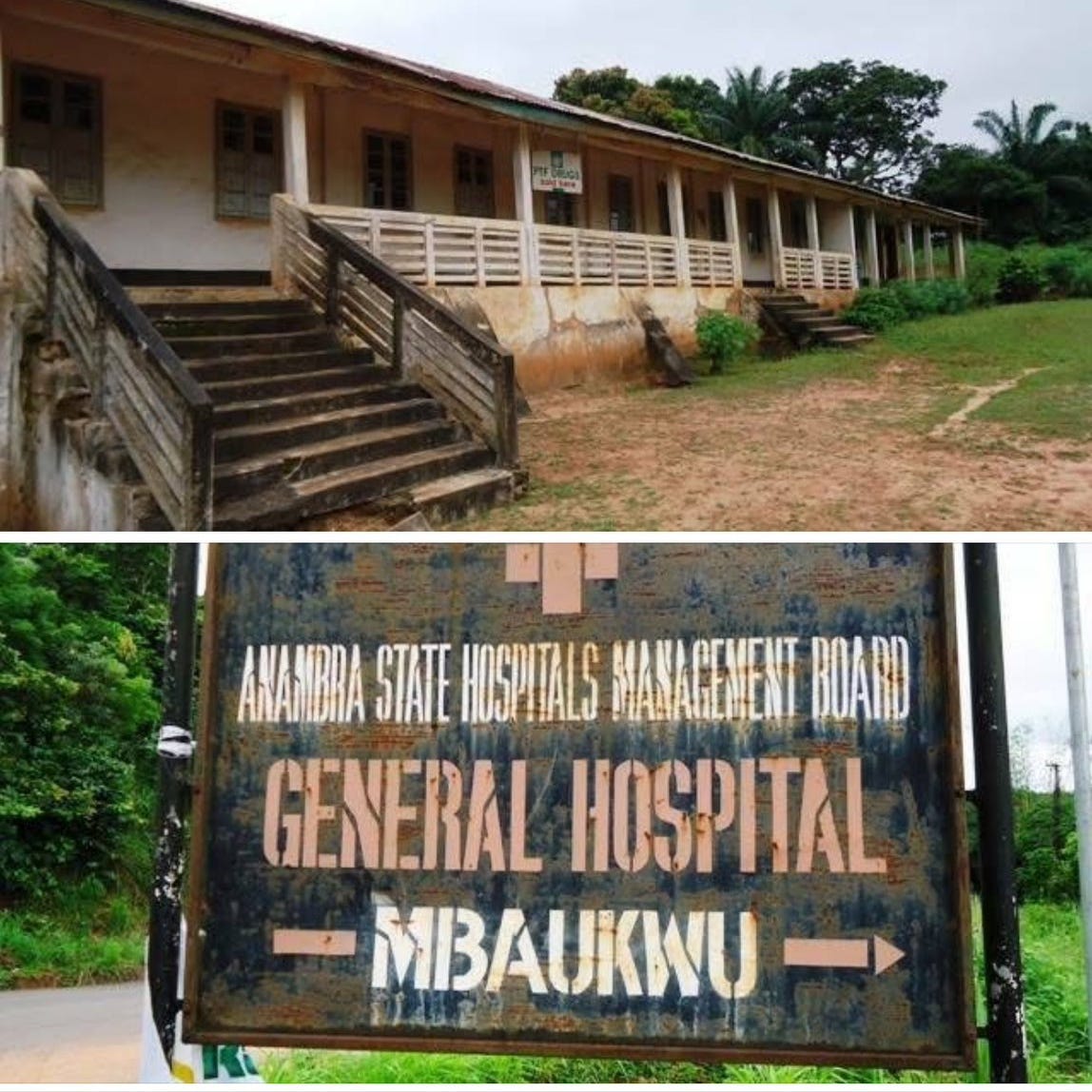

The picture below shows what moribund hospitals in our society look like, exactly the kind Dr. Neto might have closed down if he were in charge. From the image, one can imagine the supposed ‘savings’ he has in mind.

Different structures, different problems. In Denmark, hospitals were funded by municipalities, creating inequality. Reform shifted this to wealthier regions that could support better-equipped hospitals. In Nigeria, states already fund hospitals centrally. Our problem isn’t duplication or fragmentation. It’s poverty.

Geography Matters

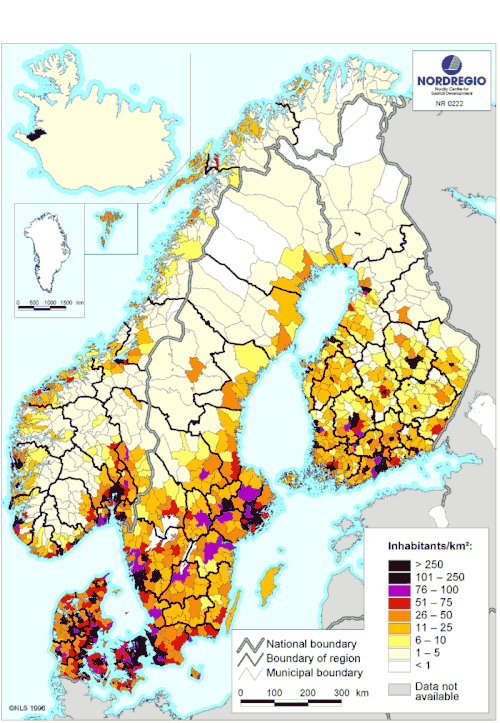

Denmark is 88% urban, with excellent transport systems, ambulance services, and even helicopters. By contrast, Akwa Ibom had only 12% urban population in 2006 (maybe about 40% today). For many rural people, the local hospital is their only access point. Closing those facilities would mean abandoning entire communities.

Fun fact, the Copenhagen region alone account for like a 3rd of Denmark's entire population.

Neto’s casual reference to Denmark’s population density is also just surface analysis. If we are citing hospitals and population, then the data should be distribution-driven, not just totals. Since healthcare is a social service, the key factor is how the population is spread. In Nigeria’s case, high-end urban centers already get the bigger hospitals and the concentration he claims is lacking, while the smaller hospitals in rural areas simply reflect our reality of population distribution.

Neto is confusing two different ailments just because the symptoms look similar. Denmark had “too much.” We have “too little.” In Denmark, too much money was stuck in a few big hospitals, while smaller ones struggled because each municipality had to manage and fund its own facilities. Nigeria is the opposite: all our facilities, both the neglected and the busy ones—are underfunded.

Our administrative structure is already centralized, and so is funding. We don’t have hospitals waiting for more patronage in order to function; they are already overstretched. To get more from our system, we don’t need fewer hospitals, we need more: more money, more staff, more facilities, more equipment.

Denmark needed structural reform to get the best out of its system, which is why it embraced centralization. Nigeria, on the other hand, already has a centralized system. What we need is adequate federal support and targeted funding. Neto’s claim of “duplication of duties” misdiagnoses the problem—what looks like duplication is in fact underfunding and resource scarcity. Almost every facility is limited to just the basics, not by choice, but by constraint.

Misdiagnosing Healthcare Demand

Dr. Neto writes as if Nigerians flood hospitals unnecessarily while Primary Healthcare Centres (PHCs) sit idle calling it an “aberration” that breeds inefficiency. That picture is detached from reality.

Here’s what really happens:

Self-medication first: Most Nigerians begin with self-diagnosis or visit local chemists (Patent Medicine Vendors) for minor illnesses.

Traditional medicine is widespread: According to Nigeria’s Federal Ministry of Health (2023), over 80% of Nigerians rely on traditional medicine as their primary care. In states like Akwa Ibom, patients also turn heavily to local chemists and patent medicine vendors, especially in rural areas, rely on traditional healers as their first line of care.

Hospitals are the last resort: By the time patients reach a hospital, their condition is usually severe — often after other options have failed.

The reason people don’t use PHCs is not “preference.” It’s because they are poorly funded, ill-equipped, and often without staff or drugs. Nigerians don’t bypass them because they’re spoiled for choice with “too many hospitals.” They bypass them because PHCs are practically useless. So when a Nigerian finally gets to a hospital, it’s because the case is dire. That hospital may still be underfunded, but it remains their only hope. Closing it doesn’t solve underfunding, it simply removes their last resort.

This is where Neto’s Denmark comparison collapses. In Denmark, people access the health system through General Practitioners (GPs) — well-funded, reliable, and universally covered under a tax-based healthcare system. In Nigeria, the equivalent entry point (PHCs) is broken, so people turn instead to chemists, traditional healers, and prayer houses until illness overwhelms them. Denmark can afford fewer hospitals because each is world-class, and every citizen has access to a GP. Though he advocated for more funding in PHCs, he still didn't touch the problem or assumed it is solved, which is where the money to fund them would come from, he based that on getting it from closed secondary facilities which isn't just going to work.

Nigeria cannot afford fewer hospitals because most citizens already live outside the formal system, relying on informal and traditional providers.

Here's a tweet picture that captures it properly from one of my favourite accounts on twitter, one I seriously recommend for nonpartisan folks.

The Budget Reality

Neto cited Akwa Ibom’s ₦9 billion allocation to its Hospital Management Board, with only ₦161 million in internally generated revenue. He interpreted this as “underutilization.” For an expert, taking that as a takeaway was shocking. Healthcare is not a profit-making venture. What matters is how much is spent relative to the population and the quality it is delivering. And ₦9 billion for nearly 5 million people is a joke.

Compare this:

Denmark spends about $5,300 (≈₦7 million) per person annually on healthcare.

Nigeria spends under $100 (≈₦150,000) per person annually.

Even if Akwa Ibom shut down half its hospitals, the money saved would be insignificant compared to the actual funding deficit. To put this into perspective: the biggest hospital in Denmark alone budgets at least 200 times what the entire Akwa Ibom health budget amounts to. Shouldn’t that mean something? Is there any sense in believing ₦9 billion can be fully “optimized” to deliver miracle-level impact for a state the size of Akwa Ibom?

Yes, money can always be spent more wisely, and prioritizing is necessary. But there is very little growth left in that margin. No improved outcome will come without building more facilities even if concentrated in a few hubs. And to be clear, in Denmark’s case, they didn’t just centralize; they also built more facilities at the focal sites to handle projected future demand. That expansion happened simultaneously, and only a rich country can afford to pull that off.

Neto is right that politicians sometimes build hospitals as photo-ops or “dividends of democracy.” But that doesn’t make them useless. People want those hospitals because they lack access, not because there are too many. Hospitals become moribund not due to lack of demand, but because there isn’t enough money to keep them functional. Closing them won’t change that.

Yes, corruption exists—politicians inflate contracts, build nonfunctional facilities, and waste funds on endless renovations. But stopping new hospital projects will not stop a corrupt politician from stealing; they will simply find other channels. What it will do, however, is leave us with fewer hospitals in a country that already doesn’t have enough. That won’t magically force politicians to prioritize the existing ones. It only worsens access.

It’s a problem, no doubt, but not the worst one to have. I would rather deal with imperfect expansion that reflects our reality than cling to an unattainable “efficiency” model that doesn’t fit our context.

Why Closing Hospitals Would Backfire

Let’s be clear: closing rural hospitals in Akwa Ibom would:

Save little money (they’re already poorly funded).

Strain urban hospitals (which are already overstretched).

Make healthcare less accessible for rural dwellers.

Increase out-of-pocket spending, pushing the poor toward chemists and quacks.

Even in Denmark, consolidation wasn’t absolute. They still maintained services in multiple sites. Neto presents it as “21 hospitals” but ignores that they still operated in 68 locations.

The Real Problem and maybe Solution

Nigeria doesn’t suffer from a structural excess of hospitals. It suffers from a financial deficit.

Our healthcare is the least socialized in the world; out-of-pocket spending is over 70%.

Our hospitals are underfunded because the country itself is poor.

Doctors and nurses are leaving because wages are low.

PHCs don’t work because they get almost no resources.

The solution isn’t to close hospitals. It’s to:

Increase healthcare budgets dramatically.

Equip both PHCs and general hospitals.

Improve rural access through roads, ambulances, and referral systems.

Expand infrastructure, not shrink it. But beneath all this is to mobilise revenue and light up our economy. Drill baby drill like my US daddy would say should be the first goal. We can't do much about our healthcare with how much we make and with our population. There's a reason we're so dependant on foreign aids. There's little to optimise in the system. We need to get money up. Like they say, until you have money before you know your real issues, you might not be wasteful, it was just never enough. To do anything we need more money, more money for more things including facilities.

Denmark’s reforms were political, funded, and consensus-driven. Nigeria cannot copy-and-paste them, because we don’t have the same base capacity. Closing hospitals was also based on that, I wish Doc Neto good luck on getting the political concensus for such in Nigeria, wouldn't even matter if he's closing down one in his village or the next.

Why This Debate Matters

I made this rebuttal because Neto’s piece feels less like a policy debate and more like a political agenda. I’m convinced it wasn’t just a random tweet that prompted him, even before reading his piece. As an expert, Dr. Neto already held such ideas, but the way they surfaced, it was clearly framed through a political lens rather than pure policy reasoning, makes the argument fundamentally flawed and inapplicable to our context.

This is not an isolated case. Intellectual dishonesty has increasingly shaped our policy conversations, often appearing whenever a political agenda is aimed at or against someone’s favorite politician. These debates, in themselves, are not bad. In fact, we need them. We need more nuance and more serious engagement. But they must come from policy angles, not partisan agendas.

For example, we shouldn’t suddenly start justifying low IGR simply because our political favorite underperformed there. Nor should we create a false debate like “HDI vs. Infrastructure” simply because one metric happens to favour our preferred candidate when in reality, the country is failing in both.

We desperately need serious, nuanced debates. What we don’t need are arguments manufactured just to counter Twitter agendas. If a political narrative is negative but factually correct, it’s better to ignore it unless you have an equally damning fact to raise about the other side. Otherwise, we just end up replacing real policy discussions with shallow partisan talking points.

Conclusion

Dr. Neto’s argument misdiagnoses Nigeria’s healthcare crisis. Our challenge is not an excess of hospitals, but a critical lack of funding, infrastructure, and access. Closing hospitals would worsen outcomes, not improve them.

The truth is simple: Nigeria is not Denmark. Akwa Ibom is not Copenhagen. Denmark dedicates approximately 10.8% of its GDP to healthcare, a GDP already larger than Nigeria’s despite having around 40 times fewer residents . By contrast, Nigeria allocates barely 0.5% of its GDP to public health spending, with total healthcare expenses covering around 3% of GDP, and more than 70% of that coming out-of-pocket .

Any comparison that omits these facts—funding levels, tax structures, insurance systems, and overall economic strength is superficial. It becomes troubling when people propose approaches rooted in abundance while ignoring that we operate in scarcity.

P.S. I could not include references and infographics I wanted because I worked on this away from home, using only my phone, and with many other agendas at hand. So you better eat

But I must add this one foot note.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168851017303500

You should write long form more frequently. This was really good 🫡

you go like replace Òdòdó?